Math of Music 1

I'm currently trying to learn the harmonica and am really enjoying it, however I have very limited understanding of how music actually works. I was a choir boy for a few years in school 1 so I can still just about sight-read a treble scale (FACE for the gaps, I forget the pneumonic for the lines, something like All Good Boys Deserve Fun?) and my brief attempts at learning the trumpet and piano have left some inkling of an understanding of harmonics as a circular structure, but beyond this I have no idea.

What I'm hoping is that there is some interesting structure to harmony and melody that can be represented mathematically, and maybe (just maybe!) this will help me on my tin sandwich escapade. I'm going to document my learning process because I want to get a better idea of how I go about learning something, but I'd also like to think that this may help my mathematically inclined brethren on their musical journey too.

Starting somewhere

Where else to begin but good old Google, I'm going to smash some buzzwords into the search bar and I will report back.

I've found a wikipedia called Music and Mathematics which seems like a great place to start. Wikipedia tends to get a bad rep sometimes but I've always found that it is excellent for mathematics, and regardless we can always check the sources.

So funnily enough I'm not the first person to ever be interested in this, in fact the Pythagoreans investigated musical scales as ratios and even made this study central to their doctrine:

"All nature consists of harmony arising out of numbers."

I'm learning that a scale is a set of pitches, each with a certain frequency (Hz). Scales repeat after exactly twice the frequency of the starting pitch, this is an octave. This must be where the Pythagoreans love of ratios comes from, octaves occur at a ratio of double the starting pitch, not after a set increment increase - news to me!

Octaves are quotient spaces?

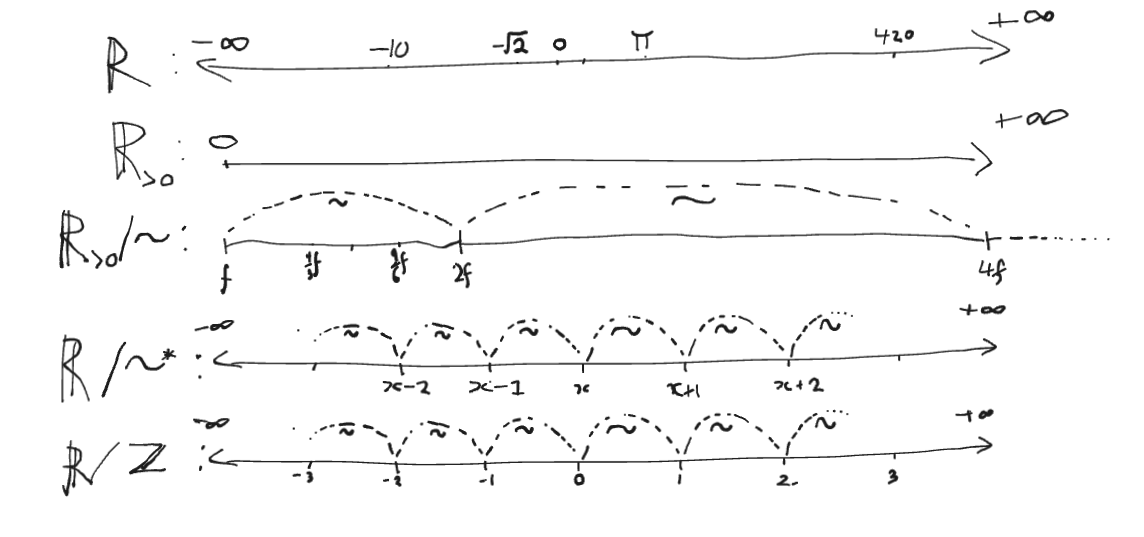

A note is the collective identity of a repeat pitch, for example is 110Hz and is 220Hz, but these are both the note . This reminds me of the mathematical concept of a quotient or identification space where the equivalence relation is defined by . This is a fancy way of saying that musical notes are the set of real numbers where if is a positive real number, the is the same as (equivalent to) .

The pitch we use to define a scale, the frequency at which the scale repeats when doubled, is called the tonic. The quotient space is symmetrical and has no distinguished reference point until we choose a tonic. If we fix a particular tonic frequency , we can define a single octave of that note as In English: The set of octaves of a tonic with frequency is all positive real numbers greater than or equal to and strictly less than .

This represents one complete cycle of pitch classes, starting from the tonic up to (but not including) its double. The set of all frequencies that belong to the same pitch class as the tonic (that is, the “same note” in any octave) is If instead we want every frequency in every octave band relative to (partitioning all positive frequencies into successive octaves), we take the union of octave intervals:

In English: for each integer , look at the interval from up to (but not including) , then take the union over all . This covers all positive frequencies, grouped into octave-wide bands.

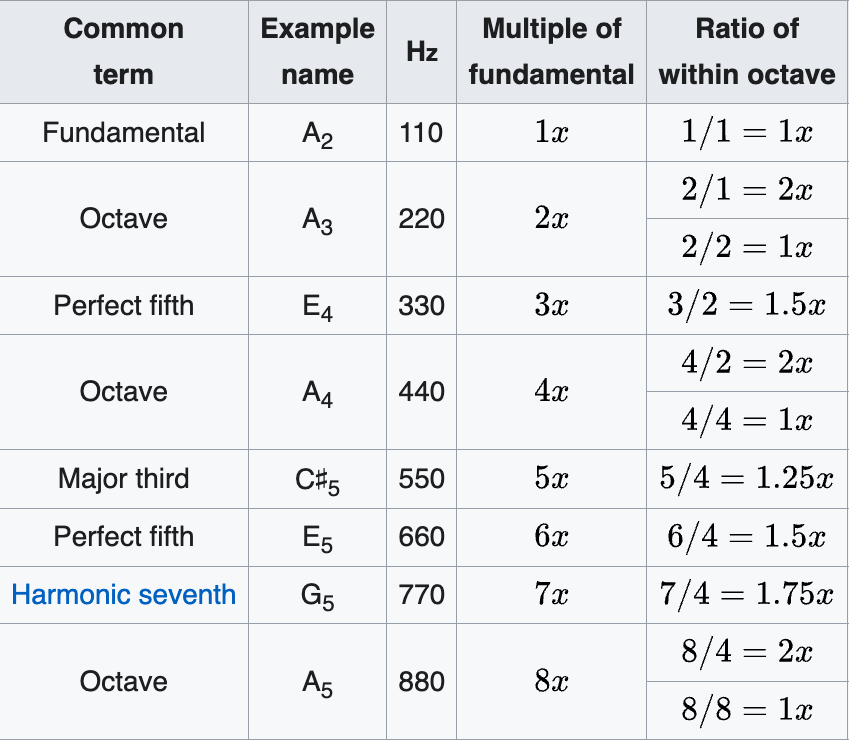

In a simple setting you can take the tonic’s frequency as the reference frequency , similar to choosing a fundamental in acoustics. Other notes at particular ratios to the tonic also have special names:

Octaves are circles!

The basis for differing notes being ratio and not increment also means that notes live on an exponential scale. So the lines on sheet music if measured by Hz would look very different indeed.

In fact, we can write our mathematical definition of an octave using this scale by taking the logarithm base 2 of the frequency hence for the relation we get

In English: If a positive real is equivalent to its double, the log base 2 of a positive real is equivalent to the log base 2 of this positive real itself plus 1.

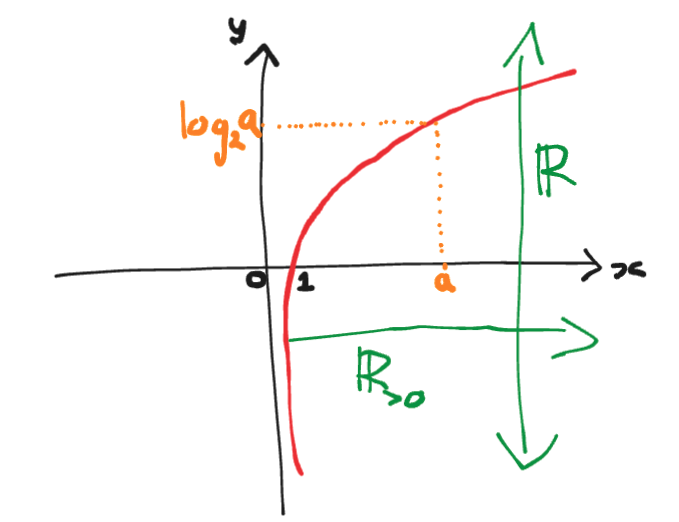

The function is bijective on , that is it has a one-to-one mapping. This is really obvious if we look at the graph.

Then we can map the whole space using our , then when we take the quotient we get where is our transformed equivalence , I'll just call it now.

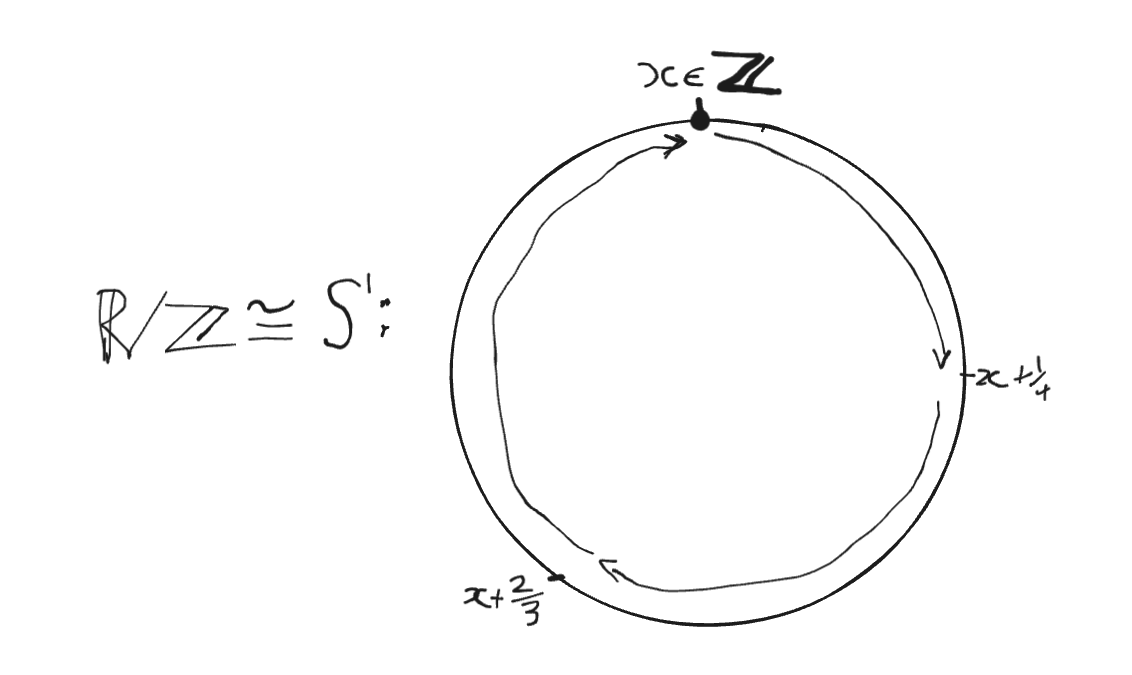

If we think about it, is the set of reals where any value is equivalent to that value plus 1, which itself is equivalent to that value plus plus 1, i.e. plus 2 2. So really what we have is any value in is the same if it differs by an integer, which is exactly , the space of real numbers where all the integers are equivalent "glued together".

Now we might say "If all the integers are actually the same value, then why don't we draw them in the same point?", that is, what happens when we glue all the integers together?

We get a circle! More precisely, consider the map Here is the imaginary unit with , and is the complex number you get by walking around the unit circle by an angle of radians. Concretely, so it always lands on the unit circle 3.

Because adding an integer to adds a whole number of full turns, the map depends only on the equivalence class of modulo . Therefore it descends to a well-defined bijection which is actually a (topological) group isomorphism. In short, So if we are being really hand-wavey, the space of notes lives on a circle which we go round and round and round as we go p or down.

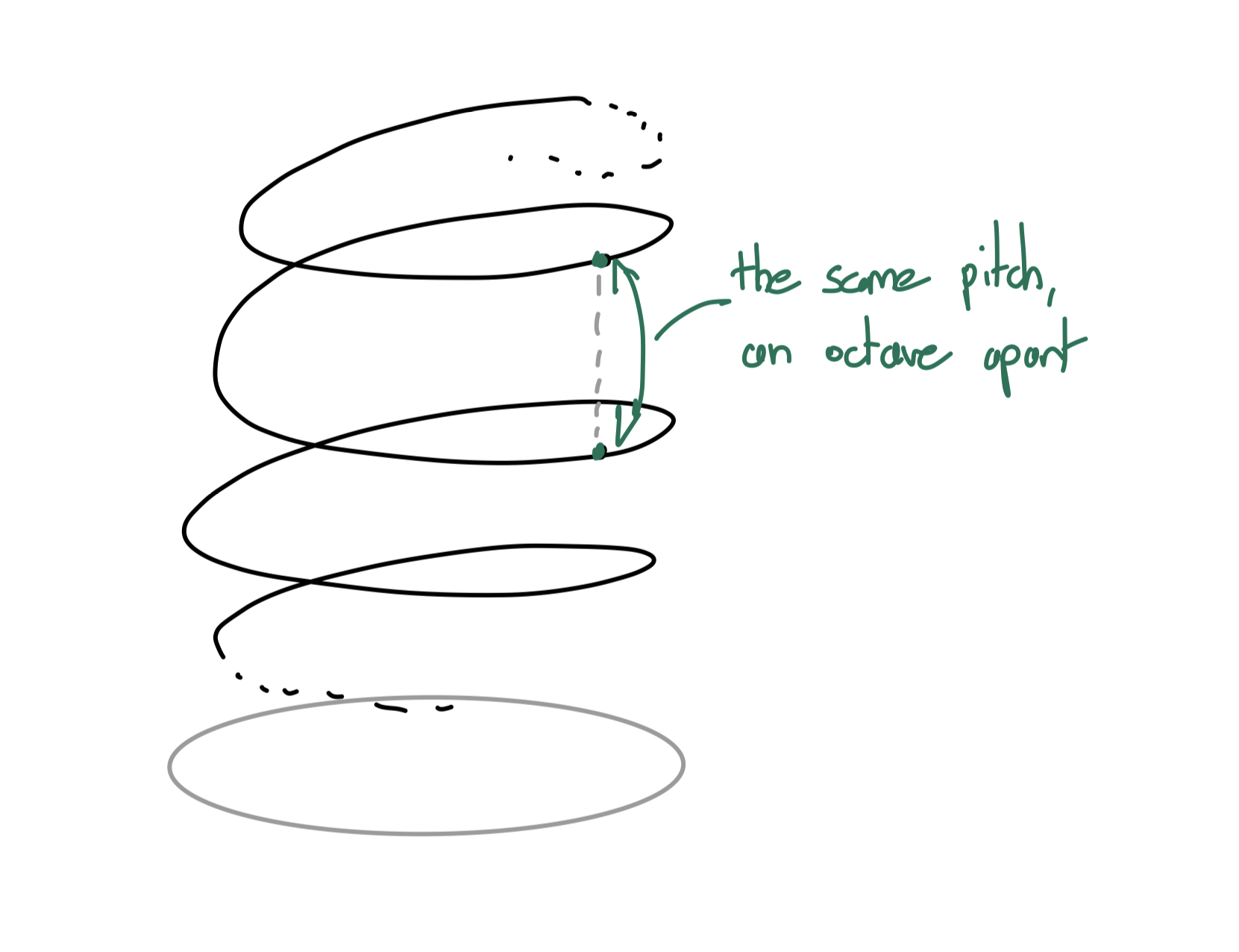

Another intuitive space to map notes too is a helix rapping around a unit cylinder, in this the angle a point in the helix makes with the centre is the pitch and the heigh is the octave we are in, so when we go around the cylinder once we are one octave above where we started, but still on the same pitch.

Formally we can write this mapping as

Harmony and the lack-there-of

So if we have nicely ratio-ed frequencies then the scale sounds pleasant and "in tune", but what if we play lots of notes at the same time i.e. a chord? I know chords can sound good or they can sound bad, this is called consonance and dissonance, which is related to but not the same as the idea of major and minor chords sounds happy or sad. We're drifting into the worlds of physics and phycology here, more specifically Psychoacoustics:

"Psychoacoustics is the branch of psychophysics involving the scientific study of the perception of sound by the human auditory system. 4"

I know there are several concepts in mathematics that are referred to as harmonic, but the relationship of these to chords is not immediately obvious. There’s simple harmonic motion, which refers to oscillations with a sinusoidal waveform; that is, those that satisfy

and have the general solution where is the amplitude and the phase.

Harmonic analysis studies functions by decomposing them into basic oscillatory pieces, like sines and cosines. A classic example is a Fourier series, which expresses a periodic function as a (possibly infinite) sum of sinusoids 5.

So if a sound is reasonably well-behaved, we can model it as built from sinusoidal components, each with its own frequency, amplitude, and phase. This does not mean the sound is “harmonic” in the musical sense, it just means sinusoids form a convenient mathematical basis for describing it.

Therefore, mathematical “harmony” (Fourier decomposition into oscillations) musical harmony (how notes and chords relate and how they feel).

To be continued...

Footnotes

-

I know, I know, but I was not half bad, with performances in St George's Chapel and on stage at the Hydro with Andrea Bucelli being just some of my career highlights. ↩

-

1+1=2 ↩

-

For those who are not familiar with this beauty i.e. Eurler's formula, to me it is one of those things in maths that is just true because of course it is. Of course you can prove it and should do at least once, but actually thinking about it too hard makes it more confusing. It's a fundamental truth, like 1 + 1 = 2 but in the complex plane, personally I do not live in the complex plane so this is not intuitive for me. Trying to break this down into why it is true every time is unnecessary work, accepting it as true and natural unlocks further understanding of concepts that rely on it. ↩